A routine hit paralyzed Kevin Kenny, yet he knows he can still contribute to the game he loves.

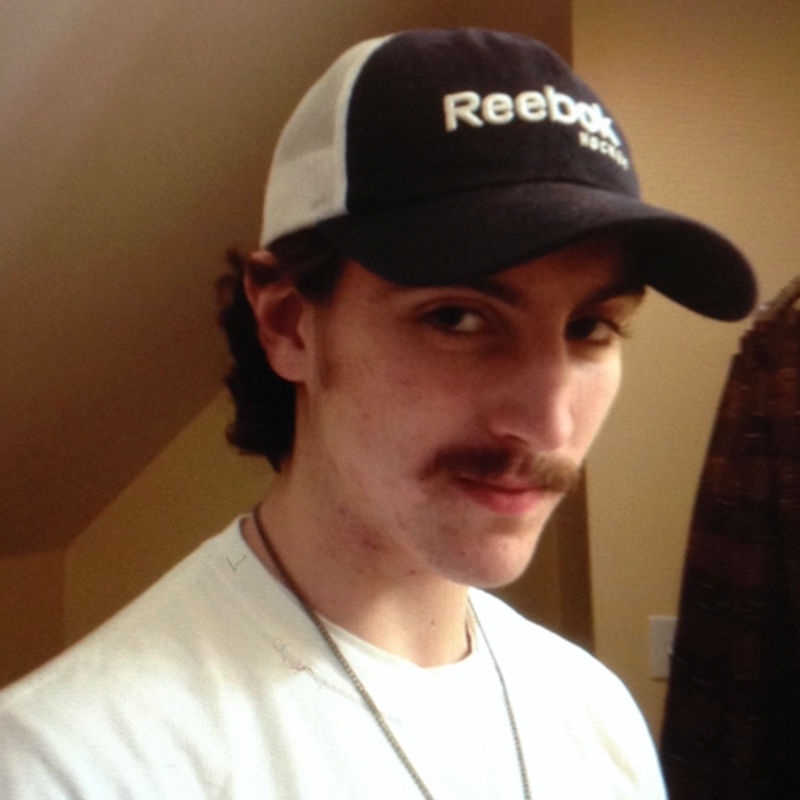

Ice hockey players—what can one say? They move faster than players in any other team sport, and elite level amateur skaters can reach speeds of 15-18 mph on 1/8” steel blades. And while they’re skating, they’re working in concert with four other skaters, deftly moving and passing a puck—and warding off hits and checks from opposing skaters. In November 2013, Kevin Kenny, center for the Pittsburgh Vengeance, a Jr. A ice hockey team, was 20 years old, and playing the best hockey of his career.

The Season To Shine

“I was playing pretty well that year,” he smiles, “I had doubled my point production from the year before at that time in the season.” He relays that he had some colleges interested in him, and things on and off the ice were going very well. (For ice hockey players that want to play in college, most play Jr. A hockey to further develop both their game and mature physically). “So, our team was on a power play, and the opponent iced the puck,” says Kenny, gesturing across his body to emphasize the icing.

A Routine Play

Kenny, as the center, skated back to gather the puck. “It was in the corner, and I took a hit that you see 100 times in a game.” Kenny pauses. Though the injury was seven and a half years ago, the incident is still fresh in his mind. “Yeah, so my back hit the boards, and then I kind of launched into the air. I might have been knocked out for five seconds, but then I was fully conscious,” he recalls, realizing he could not feel or move anything from the chest down. Kenny recounts that he was on the ice about 40 minutes before they got a stretcher.

Taco-‘Bout This!

“But what I’ll never forget,” he starts to laugh, “I really wanted tacos!” His family also hosted out-of-town players for the season (billets), and his mom would make 10 lb. of taco meat at a time. “My buddy Cody skated over to check on me, and I said, ‘Cody man, I really want some tacos right now!’” Typical hockey player—laugh off an injury and think about food. However, as Kenny was being air Medevac’d to the hospital, he realized his injury was no laughing matter.

An Army of Support

Kenny’s level of injury is C 6-7 incomplete, and his neck is fused from C4 to C7. He is blessed, even to this day, with an incredible army of family and friends for support. “In rehab I would have 20 visitors a day, so I never have really cried or gotten sad about my situation,” he says. “And, my sister has never treated me differently—to this day she still jokes about how I can’t walk!” For Kenny, this legion of support—and people that didn’t treat him differently, were some of the keys to his successful transition. One family friend allowed the Kennys to stay at a spare one-story home on their farm while an elevator was installed at their home—with donated funds. However, once the “bricks and mortar” aspects of Kenny’s home life were in place, he realized that his physical life—his body—which was his stock and trade for all of his life, was in sore need of attendance.

Lack of Follow-Up Care

And there was none available. Kenny can’t remember much of his outpatient rehab. “To be honest it all blended together with getting out of inpatient rehab,” he says. “The big thing is I didn’t have nursing care for almost two years.” Kenny and his family did not have any help after leaving the hospital, and it was left to his parents to take care of his daily needs. He now has full nursing care. “I require full assistance, he explains, noting that he has some movement in his arms, but his hands are “frozen.” “I have 12 hours a day, five days a week, and then six hours a day on the weekends. Nursing takes care of everything from getting Kenny out of bed, catheters, showers, dressing. “But!” he laughs, “I can brush my own teeth, and sometimes I can open my own water bottles!”

Pursuing A Productive Life

As a young man of 27, Kenny is eager to find work and contribute. He has a keen analytical hockey mind, and has been offered a few jobs in rinks working in hockey operations. “I’m very good with video analysis,” he says, and knows he can find a place in hockey. “There are many things that I can do,” he says, “Right now, my biggest issue that I need (a job) with insurance that will pay for nursing.” For now, Kenny engages online with high-level, interactive video games, like Twitch streaming and Fortnite (now on hold pending the lawsuit with Apple).

Paying it Forward

And he finds ways to pay it forward, just like his community did when he got injured. Last month, Kenny donated his power wheelchair to the Ryan Shazier Fund for Spinal Rehabilitation. “I met Ryan when there were peer support meetings at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC). There weren’t many younger people, so Kenny approached Shazier to see if he wanted to connect. “I followed him, and learned about the Fund, and saw that I could donate my chair, because I get a new one every five years.” For Kenny, the simple act of that donation gave him a sense of purpose. Short of getting back on the ice, finding gainful employment without compromising the care he needs will certainly be akin to scoring the game-winning goal in overtime.

Shalieve

Wisdom

Surround yourself with the right people. I wouldn't have the attitude that I do if people treated me differently. They cared enough about me to help me through all the struggles that came with the injury.

Take things one day at a time and have patience. Rome wasn’t built in a day. For instance, when I first got injured, my vocal cords were paralyzed. My dad sat next to me with a letter board, and I’d move my arm a little when he got to the letter, and that’s how I “talked.”

Keep a sense of humor. And be kind. I keep this quote in mind: “Making one person smile can change the world – maybe not the whole world, but their world.”—John Spence